When a traceability idea meets industrial reality — and fails.

Within the Commission’s proposal to replace the EU steel safeguard measure of 7 October 2025, one element stands out: the planned introduction of the “melt and pour” criterion to determine the origin of steel products. At first glance, this may seem a simple yet clever traceability improvement — a way to identify where the steel was melted and poured, giving EU trade-defence tools the means to specifically target imports from countries driving global overcapacity.

The uncomfortable truth, however, is that the melt-and-pour rule would simply curtail competition in a stainless-steel market already effectively safeguarded from unfair trade — while introducing one guarantee only: a collapse of legal certainty.

An Origin Rule With No Origins

The melt & pour requirement might appear neutral in theory, but it becomes structurally incompatible with the actual geography of stainless steel production. Outside Europe, only twelve countries are melting and pouring stainless steel. India, a major producer, is expected to fall shortly under a bilateral FTA framework that would remove it from the general regime. Yet once EU sanctions (Russia), tariff targeting (China, Indonesia), domestic or regional market orientation with little exports to the EU (United States, Japan, Brazil, South Africa), marginal producers (Canada and Ukraine) or countries primarily operating as processors of external slabs rather than smelters (Taiwan) are taken into account, eleven of these twelve origins are eliminated for practical purposes. What remains is not merely a single country but, in reality, a single producer: POSCO in South Korea.

A rule of origin that leaves only one feasible external supplier in the whole world is not a rule of origin: it is a structural market distortion. Whether by design or by accident, the melt & pour criterion would re‑engineer the EU’s stainless‑steel supply chain around a single non‑EU producer — a strategic dependency entirely at odds with the Union’s Industrial Strategy, its objectives of supply diversification and its stated desire to strengthen resilience across critical materials.

Strategic Incoherence on Industrial Autonomy

A further inconsistency arises when comparing the stated purpose of the melt-and-pour criterion with the Commission’s wider trade policy. Melt & pour is presented as a tool to shield EU steelmaking from global overcapacity; yet in stainless steel this simply means “Chindonesia” — China and its Indonesian subsidiaries that produce around 70% of the world’s stainless steel. By relying on the melt-and-pour criterion of origin, the Commission effectively targets and restricts the importation of all stainless products originally melted and poured in Chindonesia, ostensibly in the name of protecting EU steelmaking.

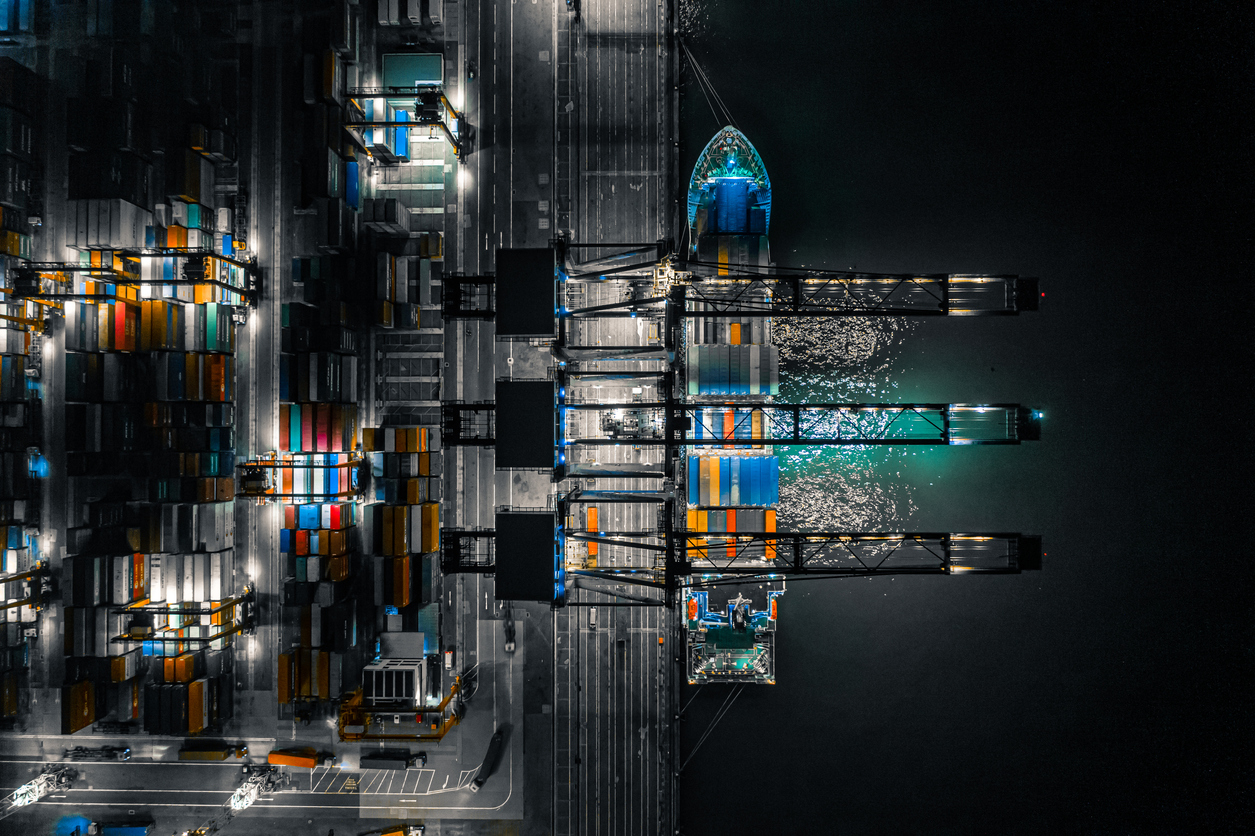

Yet the very same Commission imposes no restriction on the importation of slabs from precisely these two countries. Slabs — the first product stage after liquid steel is solidified — are not commercial end-products but feedstock used exclusively by mills. By allowing unrestricted and untaxed access to these low-priced slabs, the EU actively increases European mills’ dependence on the upstream production of the very overcapacity countries it claims to shield itself from. Judging from the exponential rise in slab imports from these origins, the EU risks, instead of preserving industrial autonomy, reducing its steelmaking to mere hot- and cold-rolling of third-country slabs — a strategically incoherent and economically unhealthy trajectory.

Misguided Narrative of “Minimal Transformation”

The very premise used to justify the melt & pour rule — the narrative that hot and cold rolling are mere “minimal transformations” routinely used to launder “Chindonesian” stainless steel through third countries — does not withstand even basic scrutiny. A hot mill or cold mill is an investment measured in hundreds of millions of euros. These are not marginal operations: they substantially transform the product by irreversibly changing its dimensions and fundamentally altering its physical, mechanical, and metallurgical properties. In economic and legal terms, this results in a new product — exactly as reflected in the existing rules of origin, which correctly assign origin to the country of the latest substantial transformation.

In stainless steel, the circumvention narrative collapses entirely. The EU market for flat products — representing more than two-thirds of all stainless imports — is already comprehensively protected. For hot-rolled stainless products, anti-dumping (AD) duties apply to China, Taiwan and Indonesia, extended to Turkey via anti-circumvention (AC) measures. For cold-rolled stainless products, protection is even broader: anti-dumping duties against China, Taiwan, Indonesia and India, combined with anti-subsidy (AS) duties on Indonesia and India, all extended to Taiwan, Turkey and Vietnam. There is simply no unaddressed loophole that melt & pour could claim to close.

Why, then, replace a coherent, legally established and operational origin system with an unverifiable and impracticable one? In a sector already fully covered by effective AD, AS, and AC measures, introducing melt & pour does not enhance enforcement — it merely creates confusion, legal uncertainty and a new administrative trap without solving any real problem.

A System as Fragile as Paper

Under the proposed melt & pour approach, “importers shall provide appropriate evidence such as a mill certificate”, to show where the raw steel was melted and poured. This declared origin would determine which country quota the imported quantity falls under, thereby abandoning the long-established principle of last substantial transformation, which remains the legal origin rule under the Union Customs Code and the basis of the current safeguard measure. That shift would mark a silent revolution in how origin is defined — replacing a rule of law with a rule of unverifiable self-declaration.

In reality, this system cannot work reliably. The traceability of steel products relies entirely on documentation. Mill certificates are merely self-declarative documents, circulating as paper or PDF files that — in today’s AI-driven environment — can be copied, altered or reused with ease — not physical identifiers indelibly linked to a specific consignment. They are not labels engraved in the metal, nor tags physically attached to the product. The documents and the material they purport to describe are entirely dissociated. Once the goods have left the mill, there is no forensic way to match one to the other.

Steel traceability therefore rests solely on good faith — a very fragile basis once significant financial liabilities depend on the certificate’s acceptance. Mill certificates can easily be adjusted “on paper” according to quota availability: a simple change in the declared origin of the hot mother coil can turn a “sensitive” origin into a “safe” one. The risk of falsification — or of simple administrative “optimisation” — would be enormous.

A Multi-stage Industry Where Origin Becomes Fiction

Steel is typically a multi-stage product. After the raw steel has been melted and poured, it undergoes several transformations — hot rolling, cold rolling, slitting, cutting, polishing, or further processing such as welded tube forming — often by different companies in different countries.

Even for cold-rolled stainless coils — still relatively early in the production chain and accounting for the largest share of the stainless quotas — the melt and pour origin of the liquid steel is impossible to verify objectively. But once those coils are cut into sheets, the challenge increases exponentially.

These sheets, which fall under the same quota category as the coils, are often certified by non-integrated service centres, one step further down the chain — where traceability can be blurred even more. At that stage, the risk of material from different origins being mixed — for instance when coils of different provenance are processed sequentially — increases significantly, making the certification of an exact melt & pour origin increasingly uncertain.

And imagine the reliability of any declared origin once those coils or sheets pass through several trading companies before reaching the EU market…

A Concept Not Yet Fit for Today’s Policy

While innovative methods such as nanomarking or blockchain-based certification are being explored and could, in theory, enable reliable traceability if adopted on a global scale, none have yet been implemented in practice across the steel industry. Existing pilot projects remain experimental, without international standards, verification authorities, or cross-border recognition. Building a verifiable, tamper-proof, and globally interoperable traceability system will take years — not months.

Basing customs duties or quota allocation on such untested technologies would be premature, and imposing them today as a market-access condition would raise serious WTO-compatibility concerns. Until then, the melt & pour criterion would solely rest on disconnected paperwork assumptions rather than on verifiable industrial facts.

Collapse of Legal Certainty

If the Commission pushes ahead before any recognised and verifiable traceability system is operational, the consequences will be severe. Sooner or later, customs authorities will realise that the documentation is unreliable. Every certificate — including genuine ones, who can tell? — will become suspect. Without any extraterritorial control capacity, each national customs administration will decide case by case, according to its own level of suspicion or pressure.

Twenty-seven different interpretations of the melt & pour rule will make compliance unpredictable. When a 50% duty is at stake, it would mean the collapse of legal certainty for EU importers — with no way to distinguish between genuine certificates, those tampered with by suppliers seeking to stay competitive, and those resulting from mutually agreed “origin adjustments”.

A Convenient Loss of Trust?

Beyond the direct commercial risk, the introduction of the melt & pour rule at this stage would seriously undermine confidence in mill certificates, which are the backbone of industrial trust.

These certificates are not mere administrative forms: they provide essential technical and quality information relied upon by thousands of EU downstream manufacturers. If their credibility were eroded, the entire European manufacturing supply chain would suffer — from processors to manufacturers and end-users.

One may legitimately wonder whether this dual consequence — the discrediting of foreign mill certificates and the legal insecurity surrounding imports— is not, for some proponents of the melt & pour criterion, a welcome collateral benefit. It would simultaneously cast lasting doubt on the reliability of non-EU products and create a hazardous and fragmented enforcement landscape marked by arbitrariness rather than legal certainty.

EURANIMI’s position

EURANIMI considers that the proposed melt and pour criterion offers no meaningful solution for the stainless-steel sector. It gives the illusion of addressing problems “at their root”, while in reality introducing incoherent and unworkable rules into a market that is already effectively protected through existing AD, AS, and AC measures. The concept rests on assumptions that simply do not apply to stainless steel and would only add legal uncertainty to a system that currently functions.

For these reasons, EURANIMI calls on the Commission to abandon the idea of introducing the melt & pour criterion for stainless steel. Its members stand ready to work with the Commission on targeted, technically grounded adjustments that would genuinely strengthen the tools already in place — whether through more precise product definitions, better articulation of substantial transformation in AC regulations, or reinforced controls on the acceptability of mill certificates at customs.

Should the Commission nevertheless persist, EURANIMI calls on it at the very least to postpone any application of the melt & pour requirement until a universally recognised, tamper‑proof, and scientifically validated traceability method has been implemented across the industry.

The United States, under its Steel Import Monitoring and Analysis (SIMA) system, has recognised this limitation: in the US, the declaration of the melt & pour origin serves purely statistical and monitoring purposes, without any impact on duties or quota allocation.

EU authorities should not reshape the customs-declaration process into a paperwork trap — transforming steel importing into a game of Russian roulette and undermining the very purpose of traceability itself.

Legal certainty is not a luxury. It is the foundation of a functioning market.

Add the weight of your voice by becoming a EURANIMI member.

Related Articles

Case Documents

Please log in as a member to consult all related case documents.